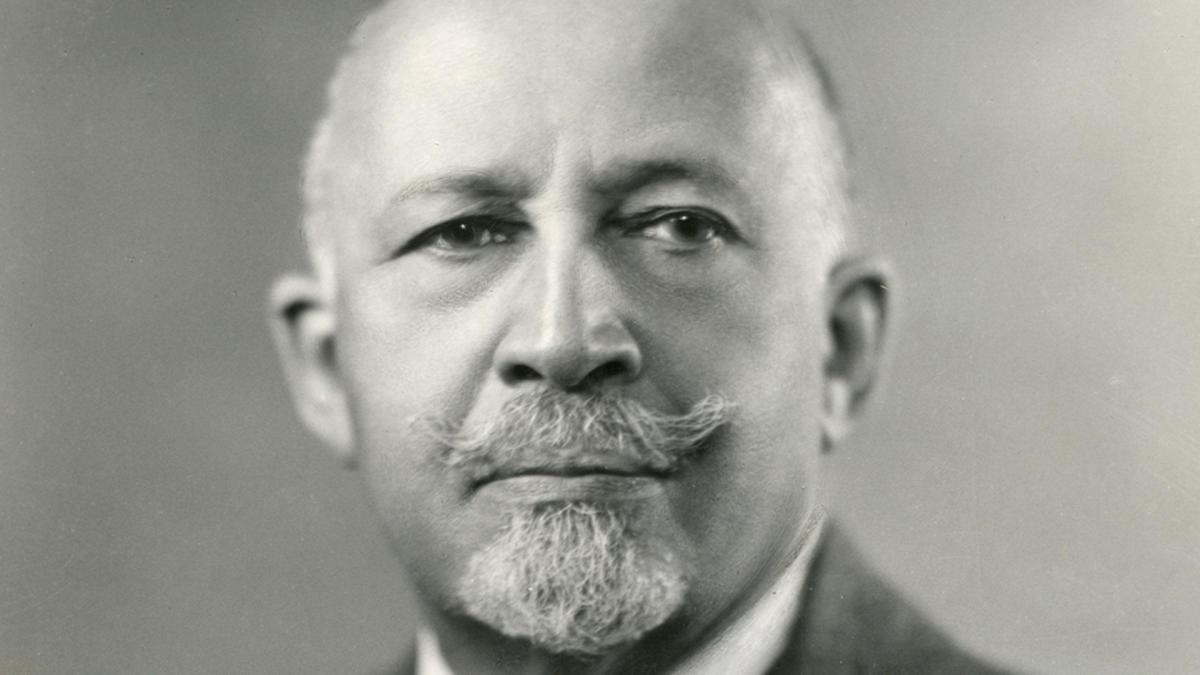

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, better known as W.E.B. DuBois was born on February 23, 1838 in Great Barrington Massachusetts. Great Barrington was a small New England town, with an even smaller black population. However, the towns’ people prided themselves on their progressive ideals, yielding a rare opportunity for black American families to thrive and raise their children without the constant barrage of race politics. Known to the town’s people as “Willie” growing up, DuBois built a reputation of a gifted child and that innate intellectual ability was not ignored. He often was among the elite students throughout his childhood and was said to have publically enjoyed that status. No matter how inflated his teenage ego may have grown as a result of constant accolades, DuBois always kept his eyes on the preverbal prize. From a young age he committed his pursuits to the study and advancement of black people. At age fifteen he became the local correspondent for the New York Globeand used the opportunity to write editorials championing the need for black people to politicize themselves. Its no wonder why DuBois would become a founding member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored people (NAACP) in 1909 along with black American pioneers Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Mary Church Terrell to name a few.

Upon graduation as high school valedictorian, he accepted a scholarship from renown historically black college, Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. Arriving at Fisk was a culture shock for young “Willie” to say the least, as he until then only encountered the frigid reality of the “Jim Crow” south in study or folklore. At the ripe age of 17 he witnessed discrimination in ways he never fathomed, however, what fueled him was the hoards of black intellectuals that also attended Fisk. It is ironic that his first encounter with blatant racism in the United States also served as his awakening to black intellectual prowess, making his dream of the advancement of his people a tangible goal, in which now he could witness with absolute certainty the goal’s attainability. His enthusiastic admittance into a large African American community is relayed in an 1886 letter to Mr. Scudder, a pastor in Great Barrington. He writes, “… I can hardly realize they are all my people; that this great assembly of youth and intelligence are representatives of a race which twenty years ago was in bondage (DuBois 1973).”

His time at Fisk was formative. He taught in rural Tennessee as a student and managed a singing group, shortly before fulfilling a life long dream of attending Harvard in which he entered as a junior. As determined, as he was to attend and graduate from Harvard, he never felt himself a part of it. Later in life he remarked, “I was in Harvard but not of it. (Almore 2011)” He received his bachelor’s degree in 1890 and immediately began working toward his master’s degree at Harvard which he completed in 1891. He chose to study at the University of Berlin in Germany for his doctorate, than considered to be one of the worlds finest institutions of higher learning, however, reluctantly completed his doctoral thesis at Harvard due to funding issues.

At the age of 26 he took a special fellowship at the University of Pennsylvania to conduct a study of black American’s as a social system. He was certain that the race problem was one of ignorance and was determined to cure color prejudice through the revelation of truth. His relentless studies led into historical investigation, statistical and anthropological measurement, and sociological interpretation. The outcome of this exhaustive endeavor was published as The Philadelphia Negro, which Elijah Anderson of UPENN Press praised as, “The Philadelphia Negro remains a classic work. It is the first, and perhaps still the finest, example of engaged sociological scholarship—the kind of work that, in contemplating social reality, helps to change it. (Anderson 2017)” This was the first time such a scientific approach to studying social phenomena was undertaken, and as a consequence DuBois is acknowledged as the father of Social Science.

With all that Dr. Dubois has done, authored The of Souls of Black Folk, a definitive work in African American literature, co-founded of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), debunked revisionist history in Black Reconstruction in America, conducted the first preeminent study in American sociology with The Philadelphia Negro, and the first negro to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University, one would assume that his legacy is cemented in black America. Unfortunately, his legacy although respected is tarnished by the controversial interpretations of “The Talented Tenth” a concept emphasizing the necessity for higher education to develop the leadership capacity among the most able 10 percent of black Americans.

The term originated in 1896 when Dr. Henry L. Morehouse, a white republican philanthropist and namesake of esteemed Morehouse College, wrote a short essay titled “The Talented Tenth“ where he argued that “an ordinary education may answer for the nine men of mediocrity (Jr. 2017),” but the properly educated talented tenth man has enormous influence and is “an uncrowned king in his sphere (Jr. 2017).” The sentiment was that gifted blacks were the only means by which the race could make progress, and, as such, they deserved opportunity for advancement.

Du Bois promoted his concept of the Talented Tenth at a time when Negroes where severely disempowered as well as disenfranchised. The time period being only 40 years after emancipation in the United States placed the Negro in a position of seeking elevation from approximately 400 years of legal chattel slavery. Needless to say, the ending of slavery did not immediately place the Negro in a position of elevation, let alone equality. Negative views and images of the Negro, who in 1903 had only recently become barely acknowledged as human, permeated American society. Most went from a position of physical enslavement to one of social and economic enslavement. A ruling regime, infuriated, insecure, and concerned that the ending of slavery would dethrone them from a position of power, reinforced negative stereotypes about Blacks and put into place numerous “separate but [not] equal” laws. Some, like Booker T. Washington, a prominent Black educator, advocated for the elevation of the Negro via the access and application of vocational/industrial education (PBS 2014). Conversely, DuBois believed and promoted the idea that formal education geared toward professions (e.g. physicians, educators, and attorneys) that did not focus on industrial trades was the ticket Blacks needed in order to board the train of elevation and empowerment. “To attempt to establish any sort of a system of common and industrial school training, without first providing for the higher training of the very best teachers, is simply throwing your money to the winds” (DuBois, The Talented Tenth 1903, 33). DuBois’s essay would passionately spell out what he perceived to be the problems of the Negro and his detailed suggestion for how to solve them, a liberal studies education being the key component of that solution. However, Du Bois recognized that not all Negroes were equipped to be leaders and elevators of the Black race.

Fast forward two centuries later and black Americans now occupy positions in business as corporate CEOs and can routinely be seen participating as high ranking government officials extending all the way to Commander-in-Chief. In 2012 Barak Obama, a Black man who shares with Du Bois an alma mater of Harvard University, was reelected as President of the United States for a second term. However, the Black masses are still in a position of disempowerment that has the critically thinking Black community questioning, “Just how far we have come?” Inquiring minds want to know if a Talented Tenth still exists. If they do, are they the arguably elitist bourgeois Du Bois seemingly characterized, and what is their responsibility to the black community? Is education still the key? These are all questions Black intellectuals grapple with.

It is important to note that DuBois ultimately foresaw the black community’s disconnect and eventually repudiated his “talented tenth” essay. In 1948, he wrote: “When I came out of college into the world of work, I realized that it was quite possible that my plan of training a talented tenth might put in control and power, a group of selfish, self-indulgent, well-to-do men, whose basic interest in solving the Negro problem was personal; personal freedom and unhampered enjoyment and use of the world, without any real care, or certainly no arousing care as to what became of the mass of American Negroes, or of the mass of any people (Feffer 2016).” DuBois went on to convey that it is not the theory that is flawed, but rather, the character of man. The rule of humanity will always skew towards an individuals personal survival over they survival of a whole community.

Despite his tireless dedication to the upliftment of Africans worldwide, many black Americans consider Dr. DuBois an elitist. I beg to differ. Yes it is true that he wrote, lived and operated completely independent of the stigmas of black life, even those proposed by black America itself. However, what his critics fail to realize is that Dr. Dubois never saw himself as the world saw him. He was truly a “freedman.” His perspective cannot be conceived by anyone living within the social mores and norms of American society. But rather, to truly understand W.E.B. DuBois as an intellectual, one must allow their mind to let go of the barrage of social constructs that plant empirical seeds into our perspectives. James Baldwin details this process in The Fire Next Timewriting,

“You were born where you were born and faced the future that you faced because you were black and for no other reason. The limits of your ambition were, thus, expected to be set forever. You were born into a society, which spelled out with brutal clarity, and in as many ways as possible, that you were a worthless human being. You were not expected to aspire to excellence: you were expected to make peace with mediocrity (Baldwin n.d.).”

DuBois was not made ashamed for his natural intellectual ability in his formative years. He was encouraged to aspire for excellence, and any black American who has suffered the harsh reality of low expectations, can imagine the freedom one must feel to not be held down with the expectations of prejudice.

Toward the end of William Edward Burghardt DuBois’s life, he too acknowledged the need for redefining his Talented Tenth theory to be one which was more inclusive. His theory took on a “double consciousness” of its own in that he came to believe and understand that “the souls of Black folks” stood to be in consistent conflict if the Black community could not be elevated with the intellectual elite working hand-in-hand with the masses. Unfortunately, this metamorphosis in ideology is one he is infrequently credited with—particularly through the lens of those who are comfortable seeing him as no more than an academic elitist. That being said, though the term may not be as relevant today as it was when it was conceived, the mission is just as valuable.

Bibliography

Almore, Alexandra L. thecrimson.October 21, 2011. http://www.thecrimson.com/article/2011/10/21/dubois-375-profile/ (accessed april 14, 2017).

Anderson, Elijah. The Philadelphia Negro – A Social Study.april 1, 2017. http://www.upenn.edu/pennpress/book/516.html (accessed april 1, 2017).

Baldwin, James. The Fire Next Time.New York: Dial Press.

DuBois, W.E.B. The Correspondence of W. E. B. Du Bois: Selections, 1877-1934.Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 1973.

—. The Talented Tenth.New York, NY: James Pott & Co. , 1903.

Feffer, John. The Fallacy of the Talented Tenth.January 1, 2016. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/john-feffer/the-fallacy-of-the-talent_b_613510.html (accessed April 1, 2017).

Jr., Henry Louis Gates. 100 Amazing Facts about the Negro.April 17, 2017. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/who-really-invented-the-talented-tenth/ (accessed April 18, 2017).

Lewis, David Levering. w.e.b. dubois biography of race 1868-1919.new york, NY: 0wl Books.

PBS. Booker T & W.E.B.january 1, 2014. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/race/etc/road.html (accessed april 1, 2017).